Abolish the Bank of England

When the Soviet Union broke up, a Russian official spoke to the economist Paul Seabright. “Please understand that we are keen to move towards a market system”, he said. “But we need to understand the fundamental details of how such a system works. Tell me, for example: who is in charge of the supply of bread to London?”

Of course, no one is in charge of the supply of bread to London. Thousands of people supply bread to London without any central plan, thanks to that amazing information processing machine, the market. It seems incredible that anyone nowadays would think a committee could plan its way through the unimaginable complexities of the economy. Yet that is exactly what the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee does when it sets its interest rate.

Price Controls

A price control is when the government sets a price. Rather than letting the market find a price where supply and demand are balanced, the government makes it illegal to sell at certain prices. The government might dictate that a good can only be sold at one price. Or they might dictate that it can only be sold for less than a certain price, or for more than a certain price. A price control will lead to a shortage or a surplus.

Price floors

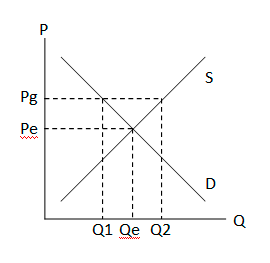

Imagine the following diagram shows the market for beans. The supply curve S shows the total amounts that will be supplied by all producers at various prices. The demand curve D shows the total amounts that will be demanded by all consumers at various prices. If the price rises, more producers will enter the market, but fewer consumers will demand the product.

Pe and Qe are the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity demanded and supplied in a free market. At that price, the quantity demanded is the same as the quantity supplied.

Imagine if the price was not at equilibrium, but was higher. Even if more suppliers didn’t enter the market to sell at these higher prices, fewer consumers would be willing to buy at that price. Suppliers wouldn’t be able to sell all their product, and would build up a surplus which they’d have to store in costly warehouses, or be forced to throw it away (also costly). To be able to sell it, they would have to sell for lower than their competitors. Every supplier thinks this, so every supplier lowers their prices; the quantity demanded increases and the market returns to equilibrium.

Imagine the government sets a price floor, a minimum price, to “help” bean farmers. A higher price is mandated, Pg. At that price, more people enter the bean market, so supply increases. But at that price, fewer consumers want to buy beans. A surplus begins to build up. A rational supplier would reduce his prices. But this is now illegal.

What happens? To try to cope with the surplus it has created, instead of simply repealing its price floor, the government will usually pass more laws to prevent farmers from entering the bean market. A so-called “black market” is usually established, which doesn’t pay attention to this law. Black markets are also known as “free markets”. Farmers are happy to get rid of their surplus product, so will sell at an illegally low price. Otherwise, a surplus builds up.

In the UK, the minimum wage is a minimum price for labour. The result is unemployment – more people looking for work than employers are willing to employ.

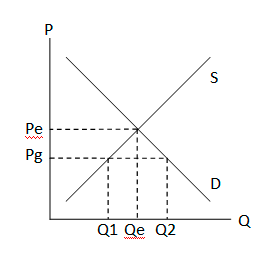

Price ceilings

If the government sets a price ceiling, or a maximum price, lower than the equilibrium price, now the quantity demanded will be higher than the quantity supplied. So there will be a deficit. This is currently happening in Venezuela and Zimbabwe. To combat high prices caused by their inflation of the currency, the governments simply imposed maximum prices. Often prices are set so low that shopkeepers are obliged to sell at a loss. The result is empty shelves.

The Bank of England’s interest rates

Interest rates are prices much like any other. Interest is the cost of capital, and the rate is determined by supply and demand. In a free market, the market would find an equilibrium price which balanced savings and loans. All money loaned out would have to have been saved by someone else.

If the government simply made it illegal to lend at more than a certain interest rate, there would be shortage of capital and the economy would suffer. More people would want to borrow at that reduced rate, but fewer savers would be willing to save at that rate. Borrowers willing to pay more would be able to do so on the black market.

So why hasn’t there been a shortage of capital? Well, there is now, causing a recession. Why wasn’t there? The answer lies in the distinction between money and capital. A government-set interest rate ceiling by itself would create a shortage of money. But rather than simply mandating that lenders not charge more than a certain amount, the government has become a lender itself through the Bank of England. Its low interest rate creates a gap between savings and lending because more people want to borrow but fewer want to lend. It plugs this gap by printing money, which it lends out itself.

Low interest rates and recession

Low interest rates in themselves, and the inflation it takes to generate them, both cause recession. They cause an artificial boom, which inevitably busts. The boom is caused by misallocation of capital, and the recession is the corrective procedure which returns the economy to efficiency.

Investment is usually funded by borrowing. A lower-than-market rate will permit less profitable, less wise, more risky investments to be made.

Inflation means that the changes in the relative structure of prices are lost in the noise of all-round price increases, caused by inflating the money supply. This hampers people from making rational choices when deciding how to allocate their capital.

These government interventions are an attempt to cause people to behave irrationally. In the short-run, they work, causing a boom. But in the long run, malinvestments will inevitably be liquidated when their unprofitability and unsustainability are inevitably realised.

In the UK, government inflation and low interest rates has lead to excessive amounts of capital being allocated to the housing market, as people came to believe that investing in property was a limitless source of wealth. This is now again realised to be false, and the bubble has now popped.

It can then be seen that low interest rates and inflation are not the solution to a recession, because they are the cause. At best, they temporarily postpone a coming recession, and because they cause more mal-investment, they make it worse. They prevent the reallocation of capital (recession) needed to make the economy more productive again.

A market interest rate will lead to the most efficient allocation of resources. Therefore the Bank of England should be abolished.

[…] that needs to be explained is the badness of the minimum wage. Just as any price-fixing will cause a shortage or a surplus, the minimum wage causes unemployment (a surplus of labour). There are some people whose labour is […]

Abolish the minimum wage « Cambridge University Conservative Association

April 2, 2009 at 8:19 am